4.4.6. Catalysts#

4.4.6.1. Motivation#

Catalysts are ubiquitous in chemistry and biology and affect the rate of reaction. They do so by affecting the overall activation energy of the reaction. This can be by directly affecting a particular activation barrier or by changing the mechanism of reaction. In these notes we will see a few examples of how a catalyst affects chemical kinetics.

4.4.6.2. Learning goals#

After working through these notes, you will be able to:

Define a catalysts

Identidy a catalyst in a reaction mechanism

Describe, qualitatively, how a catalyst enhances rates

Derive the rate equation for a catalyzed reaction

Use the rate limiting step approximation to derive rate laws for mechanisms with slow steps

4.4.6.3. Coding Concepts:#

The following coding concepts are used in this notebook:

4.4.6.4. Catalysts#

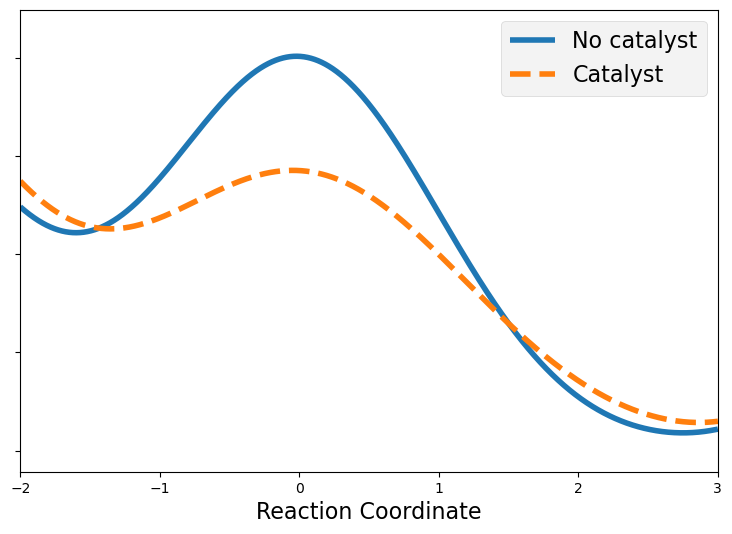

Catalysts affect the overall rate of reaction, they do not affect the Thermodynamics of the reaction. Catalysts do this by affecting the overall barrier height for a reaction by either reducing a barrier height directly or by altering the mechanism of reaction.

A catalyst is a substance that participates in a chemical reaction but is not consumed or altered by the end of the reaction. A catalysts can be modified during a reaction but it must be produced again, unaltered, by the end of the reaction.

The fact that a catalyst must be unaltered during a chemical reaction indicates that the overall Thermodynamics of the reaction are also unaltered by the presence of the catalyst. A catalyst will not make a non-spontaneous reaction become spontaneous. It will not affect the relative populations of products and reactants present at equilibrium.

4.4.6.4.1. Catalysts in an Energy Diagram Picture#

Catalysts reduce the barrier height for a chemical reaction but do not alter the relative energy of the reactants and products. This can indicated on an energy diagram by a reduced barrier height connecting the reactants and products.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from scipy.stats import norm

x_all = np.arange(-10, 10, 0.001)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9,6))

plt.style.use('fivethirtyeight')

y1= norm.pdf(x_all,0,1)

y2 = norm.pdf(x_all,-3.2,1)

y3 = norm.pdf(x_all,5.5,1)

ax.plot(x_all,y1+y2+y3,label="No catalyst")

y1= norm.pdf(x_all,0,1.2)

ax.plot(x_all,0.85*y1+1.05*y2+y3,'--',label="Catalyst")

plt.legend(fontsize=16)

ax.set_xlim([-2,3])

ax.set_xlabel('Reaction Coordinate',fontsize=16)

ax.set_yticklabels([]);

4.4.6.4.2. Catalysts in a Mechanism#

Catalysts show up in mechanisms first as a reactant and, later on, as a product. This is as opposed to an intermediate that is first produced and then consumed during a mechanism.

Consider the generic reaction

And proposed mechanism for this process of

The rate law for this mechanism can be approximated by the rate determining step and thus we have that

Note that if you used a steady-state approximation you would get a similar looking rate law of

If a catalysts is introduced into the reaction this is sometimes denoted as under or over the reaction arrow as

A catalysts, by definition, must modify the mechanism of the reaction. Here, we might propose that

Here we see that the rate law (using the rate limiting approximation) is

There are a few things to not from this expression. First is that the rate now depends on the concentration of the catalysts. This make sense. If that catalyst is binding the reactant to facilitate the formation of the product, as proposed in this mechanism, the concentration of the catalysts should affect the rate. Also, if the catalyst does lower the activation barrier of the reaction, we would expect \(k_{1,C} > k_1\) and thus for \(v_C > v\).

4.4.6.4.3. Lindemann Mechanism for Unimolecular Reactions#

One thing we have thus far overlooked is how unimolecular reactions actually occur. A unimolecular step, such as an isomerization, might look like

with corresponding rate law

But where does the energy come from. For a bimolecular (or higher molecularity) reaction, we can consider that only a fraction of collisions have enough kinetic energy to overcome the activation barrier. In unimolecular reactions, there are no collisions so why do any (or not all) molecules isomerize?

Lindemann proposed that unimolecular reactions actually occur after collision with another molecule/particle in the reaction vessel. During that collision, the other molecule inparts kinetic energy to the \(CH_3NC\) molecule ultimately providing it with enough energy to overcome the activation energy to isomerize. Thus, Lindemann proposed that a unimolecular elementary step actually proceeds as a two step mechanism

where \(M\) is some other molecule in the reaction vessel (it could be a reactant, product, carrier gas, or anything else) and \(CH_3NC(g)^*\) denotes the energized form of the molecule.

Because \(M\) is introduced as a reactant and not consumed during the reaction, it is a version of a catalyst. It is a bit untraditional as a catalyst because it might be another reactant molecule but it can still be considered a catalyst.

The rate law stemming from this mechanism, and employing the steady-state approximation, is

At high concentration we expect \(k_{-1}[M][A^*] >> k_2[A^*]\) (because collision will be frequent) or \(k_{-1}[M] >> k_2\) simplifying the rate expression to

which is first order in \([A]\) and first order overall.

At low concentration, we expect \(k_{-1}[M][A^*] << k_2[A^*]\) (because collision will be infrequent) or \(k_{-1}[M] << k_2\) simplifying the rate expression to

which is first order in \(M\) and \(A\) and second order overall. This mechanism has been demonstrated to accurately capture the transition of the rate constant from first to second order as a function of concentration for reactions such as the isomerization of \(CH_3CN\).