4.3.6. Enthalpy#

Enthalpy, \(H\), is another Thermodynamic energy (and state) function. It is an important quantity in thermochemistry. In these notes, we will see how it is related to internal energy and how it is used in the context of chemical reactions.

4.3.6.1. Learning Goals#

After these notes, you should be able to:

Express Enthalpy as a function of internal energy, pressure, and volume

Compute enthalpy from internal energy, and vice versa, for reactions involving ideal gasses

Define heat capacity at constant pressure

Compute relative enthalpies from heat capacities

Compute enthalpy changes for chemical reactions

4.3.6.2. Coding Concepts#

The following coding concepts are used in this notebook:

4.3.6.3. Enthalpy and Heat at Constant Pressure#

Heat at constant volume is equal to \(\Delta U\):

where the last equality holds for a constant volume process.

At constant pressure, heat is not equal to \(\Delta U\):

where the last equality holds because \(P = P_{ext} = constant\). We can rearrange this equation to solve for \(q_P\)

We notice that both terms on the right-hand side of this equation only depend on the initial and final state (i.e. \(\Delta U = U_{final} - U_{initial}\) and \(P\Delta V = P(V_{final} - V_{initial})\) and thus \(q_P\) is a state function. We call this state function the change in enthalpy and denote it \(\Delta H\). Enthalpy is thus defined as

4.3.6.4. Legendre Transformation#

Enthalpy and Internal Energy are related by a mathematical manipulation called a Legendre transformation. Legendre transforms are used to determine a new function that depends on the other of a conjugate pair of variables. The transformation specifically swaps the dependence of a function, \(f(x)\), on \(x\) to a new function, \(g\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right)\), on the derivative of \(f\) w.r.t \(x\). The transformation is achieved by simply substracting the product of the variable times the derivative. For example

In the context of Enthalpy and Internal Energy, we say that

We have not yet shown that \(\frac{\partial U}{\partial V} = -P\) but it does and we will discuss that later.

4.3.6.5. Example: Computing Internal Energy From Enthalpy#

The value of \(\Delta H\) at 298 K and one bar for the reaction

is -572 kJ. Compute \(\Delta U\) assuming gasses are all ideal.

For this problem we will need to use that, at constant pressure

We have \(\Delta H\) and that \(P = 1\) bar, so we just need to compute \(\Delta V\). For this problem, \(\Delta V\) is the change in volume for the reaction. So

For \(V_{reactants}\), we have three moles of ideal gas at \(P = 1\) bar so we can use the ideal gas law to compute

where I have chosen to use \(R = 0.08314\) \(L\cdot bar\cdot K^{-1}\cdot mol^{-1}\) to cancel the \(P = 1\) bar.

You could compute the volume of \(2\) moles of liquid water but you will find it to be so small that it is negligble compared to \(V_{reactants} = 74.3\) L. Thus we have that

Solving for \(\Delta U\) yields

In general, for reactions that involve ideal gasses, you get

4.3.6.6. Heat Capacity at Constant Pressure#

Heat capacity for a constant volume process is defined as

This is is not the heat capacity at constant pressure. Thus, heat capacities are path dependent. The heat capacity at constant pressure is the amount of heat it takes to raise a material/substance one Kelvin while the substance is maintained at constant pressure. The amount of heat for a constant pressure is \(q_P = \Delta H\). Thus, by analogy to constant volume, the heat capacity at constant pressure is

4.3.6.7. Relative Enthalpies can be Computed from Heat Capacities#

The definition of heat capacity at constant pressure can be rearranged to give

Integrating both sides of this equation yields

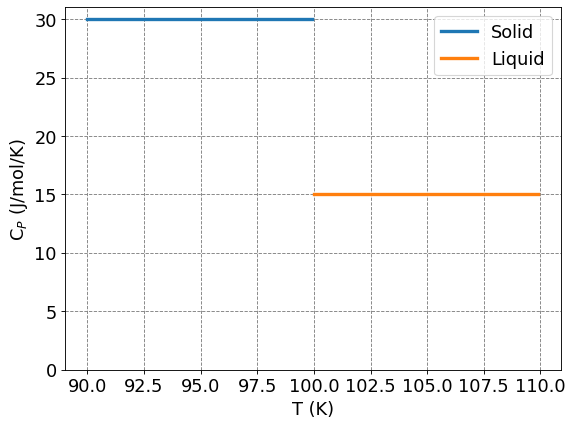

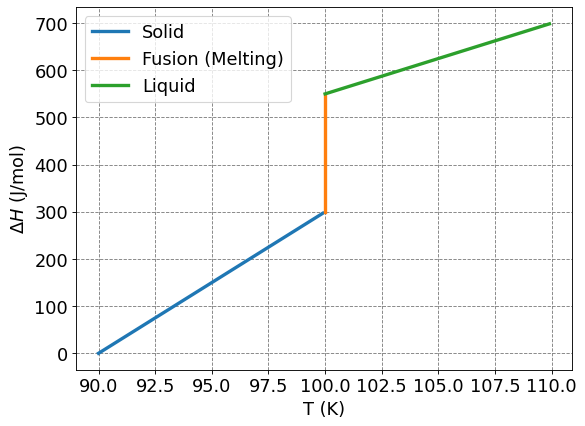

If \(C_P\) is constant, it can be taken out of the integral and you get the standard general chemistry expression that \(\Delta H = C_P \Delta T\). Generally, however, \(C_P\) will be a non-constant function of temperature and thus we will not be able to take it out of the integral.

Another difficult situation that arises is at a phase transition (e.g. vaporization or fusion/melting). At this point, the heat capacity is discontinuous and thus you cannot integrate at that temperature. If we have a situation like that, say around fusion/melting, we get that

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

def plot_Cp_v_T(Ts,Cps,Tf,Tl,Cpl,fontsize=16):

xlabel="T (K)"

ylabel="C$_P$ (J/mol/K)"

# setup plot parameters

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8,6), dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

ax = plt.subplot(111)

ax.grid(b=True, which='major', axis='both', color='#808080', linestyle='--')

ax.set_xlabel(xlabel,size=fontsize)

ax.set_ylabel(ylabel,size=fontsize)

plt.tick_params(axis='both',labelsize=fontsize)

ax.plot(Ts,Cps*np.ones(Ts.size),lw=3,label="Solid")

ax.plot(Tl,Cpl*np.ones(Tl.size),lw=3,label="Liquid")

ax.set_ylim(0,31)

plt.legend(fontsize=fontsize)

plot_Cp_v_T(np.arange(90,100,0.1),30,100,np.arange(100,110,0.1),15)

def plot_q_v_T(Ts,Cps,Tf,dHf,Tl,Cpl,Ti,fontsize=16):

xlabel="T (K)"

ylabel="$\Delta H$ (J/mol)"

# setup plot parameters

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8,6), dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

ax = plt.subplot(111)

ax.grid(b=True, which='major', axis='both', color='#808080', linestyle='--')

ax.set_xlabel(xlabel,size=fontsize)

ax.set_ylabel(ylabel,size=fontsize)

plt.tick_params(axis='both',labelsize=fontsize)

ax.plot(Ts,Cps*(Ts-Ti),lw=3,label="Solid")

ax.plot(Tf*np.ones(100),np.arange(Cps*(Tf-Ti),Cps*(Tf-Ti)+dHf,dHf/100.0),lw=3,label="Fusion (Melting)")

ax.plot(Tl,Cpl*(Tl-Ti)+Cps*(Tf-Ti)+dHf-Cpl*(Tf-Ti),lw=3,label="Liquid")

plt.legend(fontsize=fontsize)

plot_q_v_T(np.arange(90,100,0.1),30,100,250,np.arange(100,110,0.1),15,90)

4.3.6.8. Enthalpy Changes for Chemical Reactions#

The enthalpy change for a chemical reaction is an important quantity in particular for thermochemistry. An exothermic reaction is defined as one that has \(\Delta H_{rxn} < 0\) and an endothermic reaction is defined as one that has \(\Delta H_{rxn} > 0\).

Enthalpies of reactions can be estimated in a number of ways. Here we will consider two implementations of Hess’s law:

Calculating enthalpies of reactions by adding enthalpies of known reactions

Calculating enthalpies of reactions from tabulated heats of formation

4.3.6.8.1. Enthalpy of reaction by adding enthalpies of known reactions#

The heat of combustion of isobutane is \(-2869\) kJ/mol and the heat of combustion of n-butane is \(-2877\) kJ/mol. Compute the enthalpy of isomerization from n-butane to isobutane.

Start by writing out the two combustion reactions

Now we write out the final reaction that we want

In order to add the two reactions to net the reaction we want, we need to flip the second reaction and then add

The sum of these two nets the exact reaction we want and

-2877 + 2869

-8

4.3.6.8.2. Enthalpy of Reaction from Heats of Formation#

Estimate the standard heat of combustion, \(\Delta H^0_c\) of glucose (\(C_6H_{12}O_6\)(s)) given the following heats of formation

Substance |

\(\Delta H^0_f\) (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

\(C_6H_{12}O_6\)(s) |

-1260 |

\(CO_2\) (g) |

-393.509 |

\(H_2O\) (l) |

-285.83 |

We start by writing out the balanced chemical reaction

Now we compute \(\Delta H_{rxn}\)

Since the balanced reaction has one mol of \(C_6H_{12}O_6 (s)\) we can say that

6*(-393.509)+6*(-285.83)+1260

-2816.034