4.2.4. Partition Function for a Monatomic Ideal Gas#

4.2.4.1. Motivation#

We have already seen and used the partition function for an ideal gas in practice problems. Here, we will derive the form of the partition function for a monatomic ideal gas given the quantized translational energy.

4.2.4.2. Learning Goals#

After reading these notes, students should be able to:

Recognize that whenever you can write the energy of a system as a sum of independent contributions, the partition function is separable as a product of these same contributions

Recognize the translational molecular partition function

Understand the steps to go from translational energy to a translational partition function

4.2.4.3. Coding Concepts#

The following coding concepts are used in this notebook:

4.2.4.4. Energy of a Monatomic Ideal Gas#

The energy of an ideal gas with constant number of particles, \(N\), volume, \(V\), and temperature, \(T\), is a sum of energies of individual ideal gas particles. A macroscopic state, \(j\), is a sum of particle energies in that particular macroscopic state

where \(\epsilon_{i,j}\) denotes the energy of particle \(i\) in macroscopic state \(j\).

Given that we are considering our system to be a monatomic ideal gas, only the translational energy of each particle matters. Quantum mechanics gives this to be

where \(h\) is Planck’s constant, \(m\) is the mass of the particle and \(a=V^{1/3}\). Each macroscopic state will be differentiated by a the values of \(n_x, n_y, n_z\) taken on for each particle, so \(j\) is actually a list of specific values of \((n_{x,1},n_{y,1},n_{z,1},n_{x,2},..,n_{z,N})\). All macroscopic states will be accounted for by all possible combinations of \(n_x, n_y, n_z\) for each particle. Obviously, the number of possible states will thus be infinitely large.

4.2.4.5. The Canonical Partition Function of an Ideal Gas#

The canonical partition function for a monatomic ideal gas is

This can be further simplified by recognizing that the sum can be distributed over the product. Here I will just do it but we will see an example of this later.

where the notation \(\prod_{i=1}^N\) denotes the product of the argument in analogy to \(\sum\) indicating a sum and \(q_i=\sum_{n_{x,i},n_{y,i},n_{z,i}} e^{-\beta \epsilon_{1,j}}\) denotes a molecular partition function for particle \(i\).

The final steps in the derivation arise from the stiplulation that all particles be identical and indistinguishable. This has the following two results:

All \(q_i\) are identical and thus \(\prod_{i=1}^N q_i = q^N\)

The particle index \(i\) is arbitrary and thus swapping two particles (e.g. particles 2 and 4) should have no affect on the final result. This leads to an overcounting of \(N!\) per state.

Taking these two aspects into account we get:

4.2.4.6. Example: Three Ideal Gas Particles#

Consider a system of three indistinguishable ideal gas particles held at constant \(V\) and \(T\). Each particle can take on two energy levels denoted \(\epsilon_1\) and \(\epsilon_2\).

Write out all possible energy levels of the system.

Demonstrate that \(Q \approx \frac{q^N}{N!}\) for this system.

4.2.4.6.1. 1. Write out all possible energy levels#

The energy of the system is given as

where here \(j\) is as an ordered triplet, \(j = (1,2,2)\) for example, denoting the states of the three particles.

Each particle can take on one of two energy levels thus yielding a total of \(2^3=8\) possibilities

Notice, however, that there are really only four different values for the total energy. Additionally, since the particles are indistinguishable, each of the substates of the four different energy levels are indistinguishable. So really we have the following four system energy levels:

4.2.4.6.2. 2. Demonstrate \(Q \approx \frac{q^N}{N!}\).#

We have four system energy levels and can thus just write out the overall partition function for this system

A few comments on this. First, we see that we do not get, exactly, \(Q = q^N/N!\). That is because the factorial correction for indistinguishable particles is an approximation. It is technically only valid for states in which all particles occupy different states (not possible in this particular example). This is deemed a good approximation because at high enough temperature (or small enough spaced energy levels), it is likely that the particles will occupy different states.

4.2.4.7. Achieving an Analytic Solution for the Translational Partition Function#

So far we have demonstrated that, for an ideal gas, we have a Canonical partition function of the form

where \(q = \sum_je^{-\beta \epsilon_j}\) is termed the molecular partition function with molecular energy \(\epsilon_j\) for molecular state \(j\). For a monatomic ideal gas only the translational energy of each particle comes into play and thus

The goal now is to plug in the energy equation into \(q\) and derive an analytic expression for the resulting sum (and ultimately plug this result back into the above equation for \(Q\)).

We start by simply plugging in the energy into \(q\)

Where I have now labeled the molecular partition function \(q_{trans}\) to denote that it is for the translational component of the energy. We now need to evaluate the sum inside the square brackets.

In order to evaluate this sum we will make the approximation that the spacing of the translational energy levels is very small relative to \(k_BT\) and thus we can approximate the sum of quantum number \(n\) as an integral over continuous variable \(n\):

Recall from our section on continuous probability that

Thus we get that

Plugging this back into \(q_{trans}\) yields

where the last equality comes from the fact that \(a=V^{1/3}\).

Finally, we can plug this back into the equation for \(Q\) to get the final expression for the partition function of a monatomic ideal gas

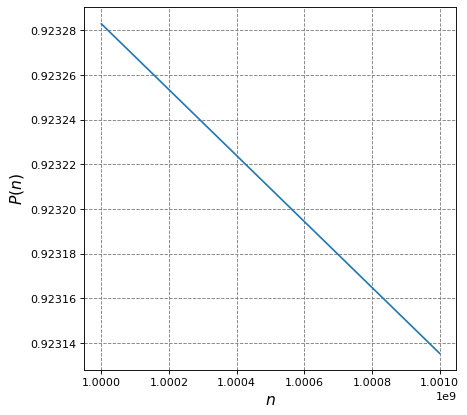

4.2.4.8. Example 1: Integration vs Summation#

Consider the following function of \(n\):

Evaluate the following two functions over domain \(1\times10^9 \leq n \leq 1.001\times10^9\) and with \(m=1\) amu, \(T=300\) K, and \(a=1\) dm.

and

import numpy as np

T = 300

kB = 1.380649e-23 # m2 kg s-2 K-1

m = 1.66e-26 # Kg

a = 1e-1 # m

h = 6.62607015e-34 # m2 kg / s

prefactor = h**2/(8*m*a**2*kB*T)

print(prefactor)

def f(n):

return np.exp(-prefactor * n**2)

7.981958150357973e-20

from scipy.integrate import quad

n = np.arange(1e9,1.001e9,1)

summation = np.sum(f(n))

numeric_integral = quad(f,1e9,1.001e9)[0]

print("Sum:", summation)

print("Integral:", numeric_integral)

print("Percent Error:", np.abs(summation-numeric_integral)/summation*100)

Sum: 923209.1920522513

Integral: 923209.1919785243

Percent Error: 7.985945991538972e-09

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

# setup plot

fontsize=14

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6,6), dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

ax = plt.subplot(111)

ax.grid(b=True, which='major', axis='both', color='#808080', linestyle='--')

ax.set_xlabel("$n$",size=fontsize)

ax.set_ylabel("$P(n)$",size=fontsize)

plt.plot(n,f(n))

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7facf27bdf40>]

4.2.4.9. Example 2: Average \(n\)#

Consider a monatomic ideal gas particle in 1D with m = 1.66x10\(^{-26}\) kg, a = 1x10\(^{-6}\) m, and T=10 K. What is the average value of the translational quantum number \(n\) assuming that it is continuous.

Some relevant equations, first the translational partition function in 1D

Next a potentially useful integral

We will also need that:

where the equation for \(\epsilon_n\) is the particle in a box energy for 1D.

The problem asks for the average \(n\), for continuous variable \(n\). This can be written as a standard weighted average

where \(P(n)\) is the probability density of variable \(n\). \(P(n)\) can be determined as the ratio of the Boltzmann factor of a particular \(n\) releative to the parition function, \(q\),

Plug this equation into the integral for \(\langle n \rangle\) yields

Now, let \(\alpha = \beta \frac{h^2}{8ma^2}\) yields

Now we can either plug in numbers or put in \(q\) as variables, simplify and then plug in numbers. Here I will do that latter:

T = 10

kB = 1.380649e-23 # m2 kg s-2 K-1

m = 1.66e-26 # Kg

a = 1e-6 # m

h = 6.62607015e-34 # m2 kg / s

print("<n> = ", np.round(4*a/h*np.sqrt(m*kB*T/(2*np.pi)),2))

<n> = 3645.94

4.2.4.10. Example 3: Order of magnitude of \(n\)#

Consider a monatomic ideal gas particle in 1D with m = 1.66x10\(^{-26}\) kg, a = 1x10\(^{-6}\) m, and T=10 K. What is the order of magnitude of the typical of the translational quantum number \(n\) assuming that it is continuous?

Additional information you will need:

To address this problem one could:

Compute \(\langle n \rangle\) as we did in the previous example

Determine the value of \(n\) that corresponds to \(\langle \epsilon \rangle\).

We will do option 2 here.

We plug-in numbers below using a code snippet.

T = 10 # K

kB = 1.380649e-23 # m2 kg s-2 K-1

m = 1.66e-26 # Kg

a = 1e-6 # m

h = 6.62607015e-34 # m2 kg / s

print("n_typical = ", np.round(np.sqrt(4*m*a**2*kB*T/h**2),2))

n_typical = 4569.51