4.5.9. Particle in a Sphere#

4.5.9.1. Motivation:#

Gearing up to work on the hydrogen atom, we recognize that the hydrogen atom is a spherically symmetric system. That is, we care about the distance of the electron from the proton/nucleus not the specific \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) coordinates of the electron. Here, we consider what constraining a particle to a sphere does as opposed to a cube.

4.5.9.2. Learning Goals:#

After working through these notes, you will be able to:

Convert between Cartesian and spherical polar coordinates

Write out the Laplacian in spherical polar coordinates

Write out the Hamiltonian for the particle in a the sphere

Perform separation of variables on the particle in a sphere Hamiltonian

Identify the solutions to the \(\phi\) differential equation

Identify the solutions to the \(\theta\) differential equation

Describe the orthonormal property of the spherical harmonics

Identify the solutions to the radial component of the particle in a sphere problem

Describe how the three quantum numbers affect the energy and wave function of the particle in the sphere.

4.5.9.3. Coding Concepts:#

The following coding concepts are used in this notebook

4.5.9.4. Statement of the Problem#

Consider a particle restricted to be in a sphere. This is equivalent to a free particle (no potential) inside a fixed radius and an infinte potential at \(r_0\).

We would like to know the allowed energies and probability of positions for such a system. To get these we will setup and solve the Schrodinger equation.

We start by defining the Hamiltonian for such a system.

4.5.9.5. The Hamiltonian#

We start constructing the Hamiltonian in the same way for every problem. The Hamiltonian is always (for the sake of this class/these notes) a sum of the Kinetic Energy operator and the Potential Energy operator:

The potential energy for this problem is zero since the particle is free inside the sphere and cannot go outside of the sphere. Thus

The Kinetic Energy operator in three dimensions for a single particle is

We could attempt to solve this problem in Cartesian coordinates. Solving the differential equation will yield the same initial solutions as the 3D particle in a box:

where the total wavefunction is \(\psi(x,y,z) = X(x)Y(y)Z(z)\)

The issue is that applying the boundary condition that

is difficult in Cartesian coordinates in part because it requires a coupling of \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\). Instead, we will solve the problem in spherical polar coordinates.

4.5.9.6. Spherical Polar Coordinates#

In spherical polar coordinates, we define a point in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) by a distane from the origin, \(r\), and two angles, \(\theta\) and \(\phi\).

These can be expressed in terms of Cartesian coordinates as

Note that the following domain limits are placed on these coordinates

The Cartesian coordinated in terms of their spherical counterparts are:

In order to describe the particle in a sphere problem in spherical coordinates, we need to define the Hamiltonian in spherical coordinates. This can be done with the equations above and their derivatives and second derivatives. The derivation is long and tedious so here we present the result for the Laplacian in spherical polar coordinates:

4.5.9.7. Separation of Variables in Spherical Coordinates#

The Schrodinger equation in spherical polar coordinates is

This equation does not look immediately separable. Indeed it looks quite intimidating. It turns out, however, that the equation is separable into \(r\), \(\theta\), and \(\phi\) components. We will start by separating \(r\) from \(\theta\) and \(\phi\).

Multiply both sides of the above equation by \(2mr^2\) to get

Rearrange (combine terms dependent on \(r\)) to get

Notice that we have a sum of a term that depends on \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) and then two terms that depend only on \(r\). Thus we can posit a separation of variables such that

Additionally, we will define the angular momentum operator (that only operates on \(\theta\) and \(\phi\)) as

Substite the above equation for \(\psi\) into the Schrodinger equation to get

Notice that the left-hand side depends on \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) only and the right-hand side depends on \(r\) only. Thus, we must have that

where \(\alpha\) is a constant.

Additionally, we must have that

We will solve these two equations separately.

4.5.9.8. Solutions to \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) equation#

It is the goal of this section of the notes to find a solution to the differential equation

where \(\alpha\) is a constant.

This equation can be rearranged to the eigenvalue equation

Now plugging back in the expanded form of \(\hat{L}^2\) we get

Multiplying the above equation by \(\sin^2\theta\) yields

We notice that this motivates a separation of variables into

Substituting this and \(\beta = \frac{\alpha}{\hbar^2}\) yields

Divide both sides of the equation above by \(\Theta(\theta)\Phi(\phi)\) and note that the operator on the right-hand side is independent of \(\theta\) to yield

Now the left-hand side is independent of \(\phi\) and the right-hand side is independent of \(\theta\). Since these two things are equal but independent of the other’s variable they must be constant. We will define this constant as \(m^2\) (for reasons that will become clear later) and solve the following two equations independently

\(m^2 = -\frac{1}{\Phi(\phi)}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial^2\phi} \Phi(\phi) \tag{1}\)

\(m^2 = \frac{\sin\theta}{\Theta(\theta)}\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\left(\sin\theta\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\right)\Theta(\theta)+\beta\sin^2\theta \tag{2}\)

4.5.9.8.1. Solutions to \(\phi\) equation (1)#

Equation (1) above can me simply rearranged to give

\(-m^2 \Phi(\phi)= \frac{\partial^2}{\partial^2\phi} \Phi(\phi)\)

which is straightforward eigenvalue-eigenvector problem with solutions

\(\Phi(\phi) = A_me^{im\phi}\quad \mathrm{and}\quad A_{-m}e^{-im\phi}\).

Applying boundary conditions, \(\Phi(\phi+2\pi) = \Phi(\phi)\) yields the quantization

\(m=0,\pm 1, \pm 2, ...\)

Thus we can write

\(\Phi(\phi) = Ae^{im\phi} \quad m=0,\pm 1, \pm 2, ...\).

Normalization yields \(A=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\).

4.5.9.8.2. Solutions to \(\theta\) equation (2)#

The solutions to equation (2) above are not as straightforward as those for equation (1). We start by rewriting the original equation here:

\(m^2 = \frac{\sin\theta}{\Theta(\theta)}\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\left(\sin\theta\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\right)\Theta(\theta)+\beta\sin^2\theta\).

Now make a change of variable \(x = \cos\theta\) which yields \(\frac{dx}{-\sin\theta}=d\theta\) and define \(P(x) = \Theta(\theta)\). Plugging these in an performing some rearrangements yields the Legendre equation

\((1-x^2)\frac{d^2}{dx^2}P(x)-2x\frac{d}{dx}P(x)+\left[\beta-\frac{m^2}{1-x^2}\right]P(x) = 0\).

For \(\Theta(\theta)\) to be continous \(\beta=l(l+1)\) where \(l=0,1,2...\). Note that this also puts a limit on \(m\) with \(m=0,\pm 1, \pm 2, ... , \pm l\).

The solutions, \(P(x)\), to the Legendre equation are known as the Associated Legendre polynomials.

\(P_l^m = (-1)^m(1-x^2)^{m/2}\frac{d^m}{dx^m}P_l(x)\)

where

\(P_l(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\frac{(-l)_k(l+1)_k}{k!^2}\left(\frac{1-x}{2}\right)^k\)

and \((l)_k = \frac{(l+k-1)!}{(l-1)!}\).

Below is a table of the first few associated Lengedre polynomials followed by a plot of these functions

\(l\) |

\(m\) |

\(P_l^m(x)\) |

|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

\(P_0^0(x) = 1\) |

\(1\) |

\(-1\) |

\(P_1^{-1}(x) = \frac{1}{2}\sqrt{1-x^2}\) |

\(1\) |

\(0\) |

\(P_1^{0}(x) = x\) |

\(1\) |

\(1\) |

\(P_1^{-1}(x) = -\sqrt{1-x^2}\) |

Show code cell source

# plot of some of the Legendre polynomials

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from scipy.special import lpmv

x = np.arange(-1,1,0.0001)

plt.figure(figsize=(12,6),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

plt.tick_params(axis='both',labelsize=20)

plt.grid(b=True, which='major', axis='both', color='#808080', linestyle='--')

for l in range(2):

for m in range(-l,l+1):

label = "l=" + str(l) + ", m=" + str(m)

plt.plot(x,lpmv(m,l,x),lw=4,label=label)

plt.title("Associated Lengedre Polynomials",fontsize=16)

plt.legend(fontsize=16);

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[1], line 11

9 plt.figure(figsize=(12,6),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

10 plt.tick_params(axis='both',labelsize=20)

---> 11 plt.grid(b=True, which='major', axis='both', color='#808080', linestyle='--')

12 for l in range(2):

13 for m in range(-l,l+1):

File /opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.13/site-packages/matplotlib/pyplot.py:3396, in grid(visible, which, axis, **kwargs)

3389 @_copy_docstring_and_deprecators(Axes.grid)

3390 def grid(

3391 visible: bool | None = None,

(...) 3394 **kwargs,

3395 ) -> None:

-> 3396 gca().grid(visible=visible, which=which, axis=axis, **kwargs)

File /opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.13/site-packages/matplotlib/axes/_base.py:3357, in _AxesBase.grid(self, visible, which, axis, **kwargs)

3355 _api.check_in_list(['x', 'y', 'both'], axis=axis)

3356 if axis in ['x', 'both']:

-> 3357 self.xaxis.grid(visible, which=which, **kwargs)

3358 if axis in ['y', 'both']:

3359 self.yaxis.grid(visible, which=which, **kwargs)

File /opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.13/site-packages/matplotlib/axis.py:1735, in Axis.grid(self, visible, which, **kwargs)

1732 if which in ['major', 'both']:

1733 gridkw['gridOn'] = (not self._major_tick_kw['gridOn']

1734 if visible is None else visible)

-> 1735 self.set_tick_params(which='major', **gridkw)

1736 self.stale = True

File /opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.13/site-packages/matplotlib/axis.py:960, in Axis.set_tick_params(self, which, reset, **kwargs)

947 """

948 Set appearance parameters for ticks, ticklabels, and gridlines.

949

(...) 957 gridlines.

958 """

959 _api.check_in_list(['major', 'minor', 'both'], which=which)

--> 960 kwtrans = self._translate_tick_params(kwargs)

962 # the kwargs are stored in self._major/minor_tick_kw so that any

963 # future new ticks will automatically get them

964 if reset:

File /opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.13/site-packages/matplotlib/axis.py:1109, in Axis._translate_tick_params(cls, kw, reverse)

1107 for key in kw_:

1108 if key not in allowed_keys:

-> 1109 raise ValueError(

1110 "keyword %s is not recognized; valid keywords are %s"

1111 % (key, allowed_keys))

1112 kwtrans.update(kw_)

1113 return kwtrans

ValueError: keyword grid_b is not recognized; valid keywords are ['size', 'width', 'color', 'tickdir', 'pad', 'labelsize', 'labelcolor', 'labelfontfamily', 'zorder', 'gridOn', 'tick1On', 'tick2On', 'label1On', 'label2On', 'length', 'direction', 'left', 'bottom', 'right', 'top', 'labelleft', 'labelbottom', 'labelright', 'labeltop', 'labelrotation', 'grid_agg_filter', 'grid_alpha', 'grid_animated', 'grid_antialiased', 'grid_clip_box', 'grid_clip_on', 'grid_clip_path', 'grid_color', 'grid_dash_capstyle', 'grid_dash_joinstyle', 'grid_dashes', 'grid_data', 'grid_drawstyle', 'grid_figure', 'grid_fillstyle', 'grid_gapcolor', 'grid_gid', 'grid_in_layout', 'grid_label', 'grid_linestyle', 'grid_linewidth', 'grid_marker', 'grid_markeredgecolor', 'grid_markeredgewidth', 'grid_markerfacecolor', 'grid_markerfacecoloralt', 'grid_markersize', 'grid_markevery', 'grid_mouseover', 'grid_path_effects', 'grid_picker', 'grid_pickradius', 'grid_rasterized', 'grid_sketch_params', 'grid_snap', 'grid_solid_capstyle', 'grid_solid_joinstyle', 'grid_transform', 'grid_url', 'grid_visible', 'grid_xdata', 'grid_ydata', 'grid_zorder', 'grid_aa', 'grid_c', 'grid_ds', 'grid_ls', 'grid_lw', 'grid_mec', 'grid_mew', 'grid_mfc', 'grid_mfcalt', 'grid_ms']

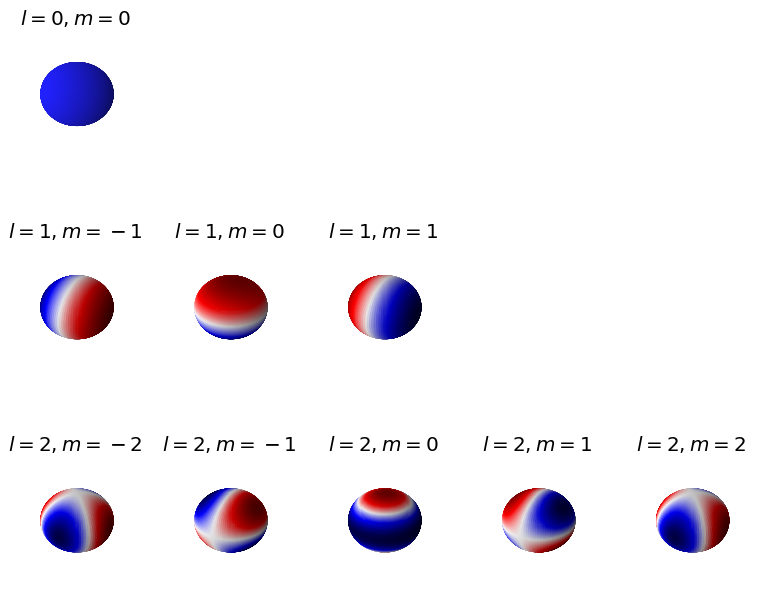

4.5.9.8.3. Combining Solutions to \(\theta\) and \(\phi\)#

The total wavefunctions are the product of \(\Phi(\phi)\) and \(\Theta(\theta)\). It is easy to see

\(Y_l^m(\theta,\phi)\propto P_l^{|m|}(\cos\theta)e^{im\phi}\).

These are the spherical harmonics. We will now look at some of these.

Show code cell source

# make two plots of the same spherical harmonic

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from matplotlib import cm, colors

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.special import sph_harm

%matplotlib inline

from scipy.special import sph_harm

def plot_spherical_harmonic(m,l, ax_obj, theta=np.linspace(0,np.pi,100),phi=np.linspace(0,2*np.pi,100)):

THETA, PHI = np.meshgrid(theta, phi)

X = np.sin(THETA) * np.cos(PHI)

Y = np.sin(THETA) * np.sin(PHI)

Z = np.cos(THETA)

# Calculate the spherical harmonic Y(l,m) and normalize to [0,1]

fcolors = sph_harm(m, l, PHI, THETA).real

fmax, fmin = fcolors.max(), fcolors.min()

if l>0:

fcolors = (fcolors - fmin)/(fmax - fmin)

# plot

ax_obj.set_title(rf'$l={l},m={m}$', fontsize=18)

ax_obj.plot_surface(X, Y, Z, rstride=1, cstride=1, facecolors=cm.seismic(fcolors))

ax_obj.set_axis_off()

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3,5,figsize=(12,10),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k',subplot_kw={'projection': '3d'})

for i in range(3):

for j in range(5):

ax[i,j].set_axis_off()

for l_index, l in enumerate(range(3)):

for m_index, m in enumerate(range(-l,l+1)):

plot_spherical_harmonic(m,l,ax[l_index,m_index])

plt.show();

4.5.9.9. Solution to the \(r\) differential equation#

It is the goal of this section to solve the equation

The above equation is a form of the radial component of the Helmholtz equation and has the solution of the spherical Bessel functions.

Plugging in what we have already determined for \(\alpha\) (namely \(\alpha = \hbar^2\beta = \hbar^2l(l+1)\))

Multiplying through by \(-\frac{R(r)}{2m}\) and rearranging yields

We now make the substitution that \(u(r) = rR(r)\). This will allow us to simplify the above equation due to the fact that

Making this substition yields

Dividing through by \(r\) yields

We note that this final expression looks like a Schrodinger equation in \(r\) with a potential of \(-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{l(l+1)}{r^2}\). This potential has the effect of pushing the particle away from the origin and is thus sometimes referred to as the centrifugal potential.

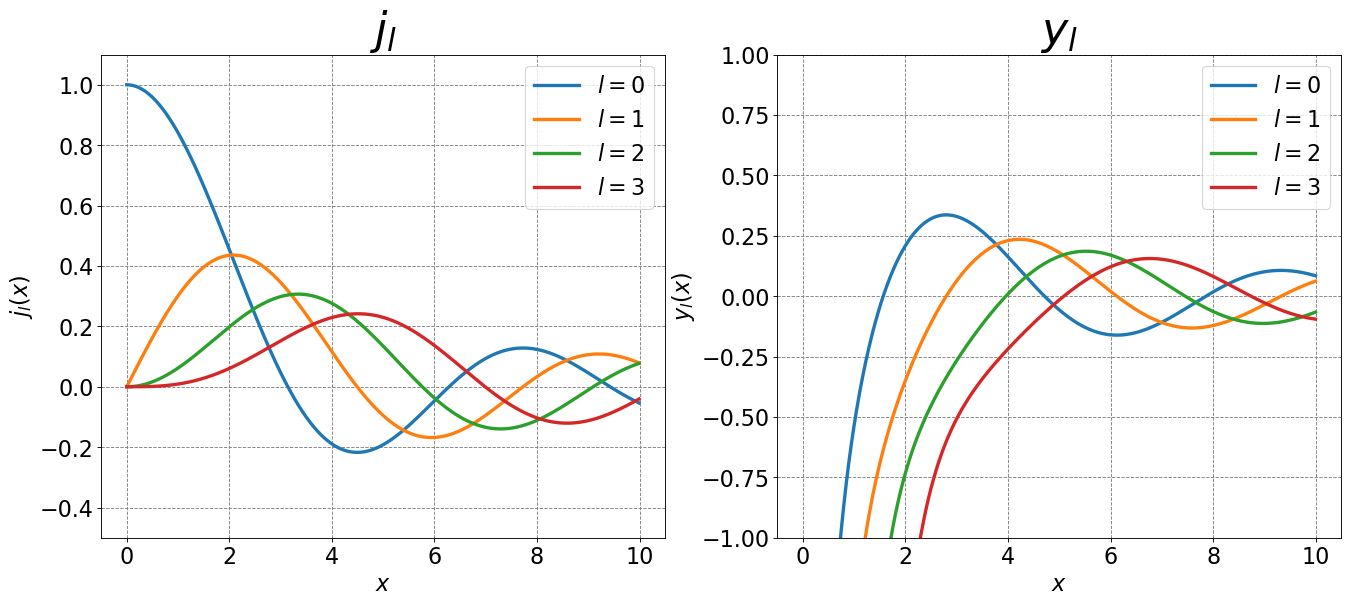

The solutions to this differential expression are related to the spherical Bessel functions with a general solution written as

where \(A\) and \(B\) are constants, \(k=\sqrt{\frac{2mE}{\hbar^2}}\) and \(j_l\) (spherical Bessel functions of type 1) and \(y_l\) (spherical Bessel functions of type 2) are defined as

Below are plots of the first few of both of these functions.

Show code cell source

#### import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from scipy.special import spherical_jn, spherical_yn

fontsize = 20

x = np.arange(0.0, 10.0, 0.01)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=(20,8),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

ax[0].set_ylim(-0.5, 1.1)

ax[0].set_title(r'$j_l$', fontsize=2*fontsize)

ax[0].set_xlabel(r'$x$',size=fontsize)

ax[0].set_ylabel(r'$j_l(x)$',size=fontsize)

ax[0].tick_params(axis='both',labelsize=fontsize)

for n in np.arange(0, 4):

ax[0].plot(x, spherical_jn(n, x), lw = 3, label=rf'$l={n}$')

ax[0].grid(b=True, which='major', axis='both', color='#808080', linestyle='--')

ax[0].legend(loc='best',fontsize=fontsize)

# second type

ax[1].set_ylim(-1, 1)

ax[1].set_title(r'$y_l$',fontsize=2*fontsize)

for n in np.arange(0, 4):

ax[1].plot(x, spherical_yn(n, x), lw = 3, label=rf'$l={n}$')

ax[1].set_xlabel(r'$x$',size=fontsize)

ax[1].set_ylabel(r'$y_l(x)$',size=fontsize)

ax[1].tick_params(axis='both',labelsize=fontsize)

ax[1].legend(loc='best',fontsize=fontsize)

ax[1].grid(b=True, which='major', axis='both', color='#808080', linestyle='--')

plt.show();

From the above plots we observe that both \(j_l\) and \(y_l\) are single-valued and continuous over the plotted domain. Additionally, the \(j_l\) functions are all finite over the plotted domain. The \(y_l\) functions, however, are not finite over the domain as they tend to \(-\infty\) as \(x\rightarrow0\). Thus, we get the solutions

or

Applying the boundary condition that

yields

where \(\beta_{n,l}\) is the \(n\)th root (\(n=1,2,3...\)) of the \(l\)th spherical Bessel function of the first type. There are an infinite number of zeros for each \(l\). The values of these zeros cannot, in general, be determined analytically (except for \(l=0\)). Here is a table of some of the zeros

l\n |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0 |

\(\pi\) |

\(2\pi\) |

\(3\pi\) |

\(4\pi\) |

1 |

4.493 |

7.725 |

10.904 |

14.066 |

2 |

5.763 |

9.095 |

12.322 |

15.515 |

From the equation \(kr_0 = \beta_{n,l}\) we can also get the energy using the previously stated equality \(k = \sqrt{\frac{2mE}{\hbar^2}}\)

Also, the radial wavefunction is now

4.5.9.10. Combined Solution for the wave functions#

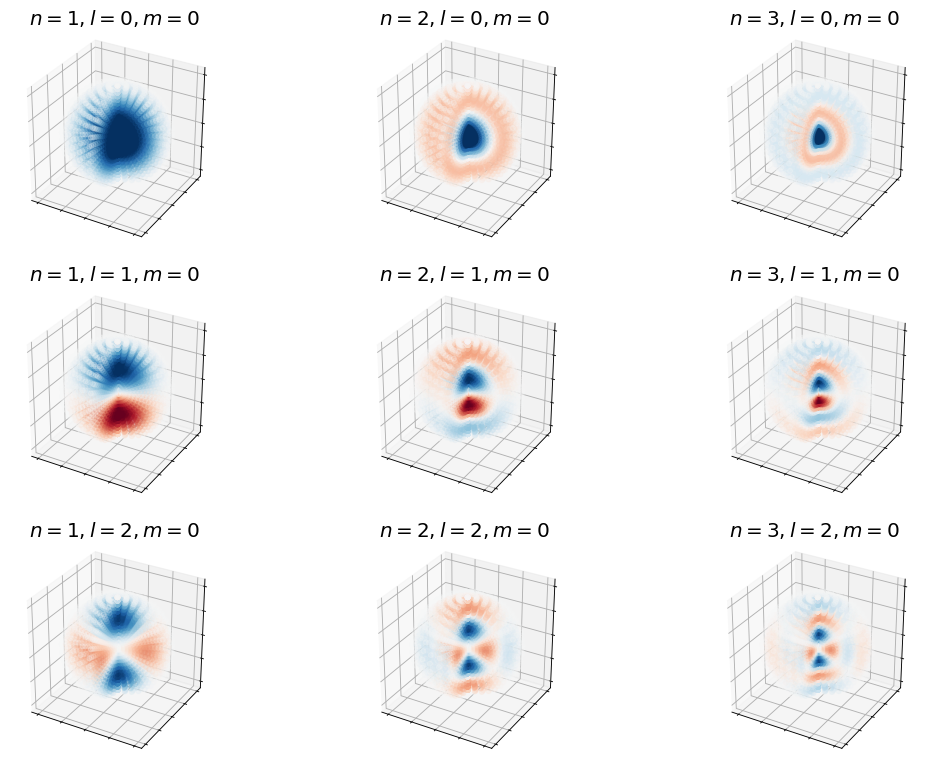

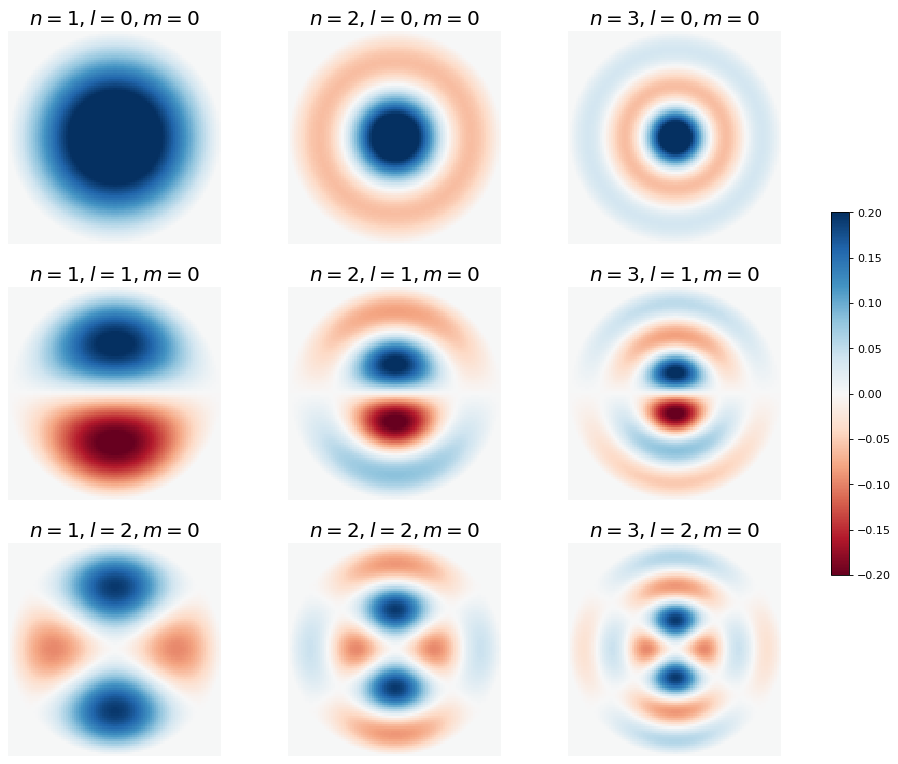

We can now combine our solutions for the wave functions for \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) and \(r\) to get

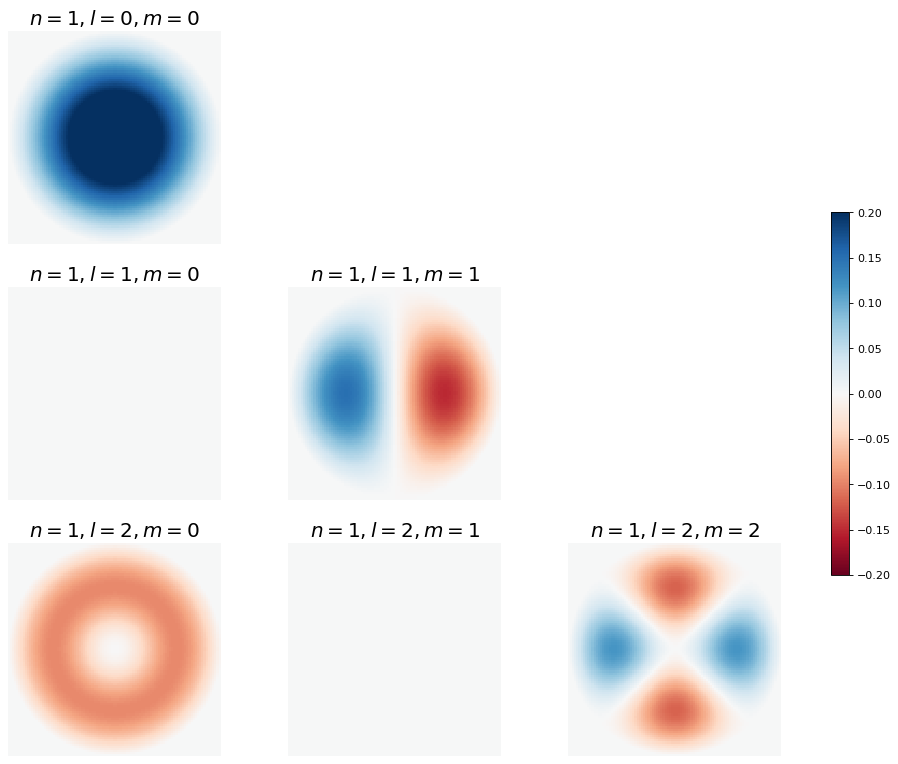

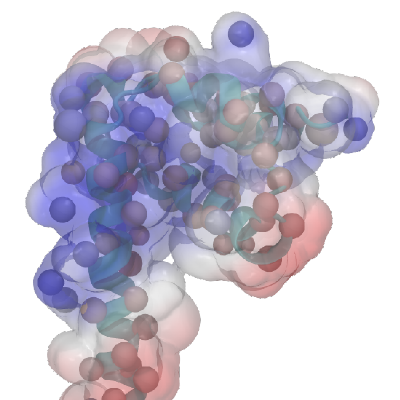

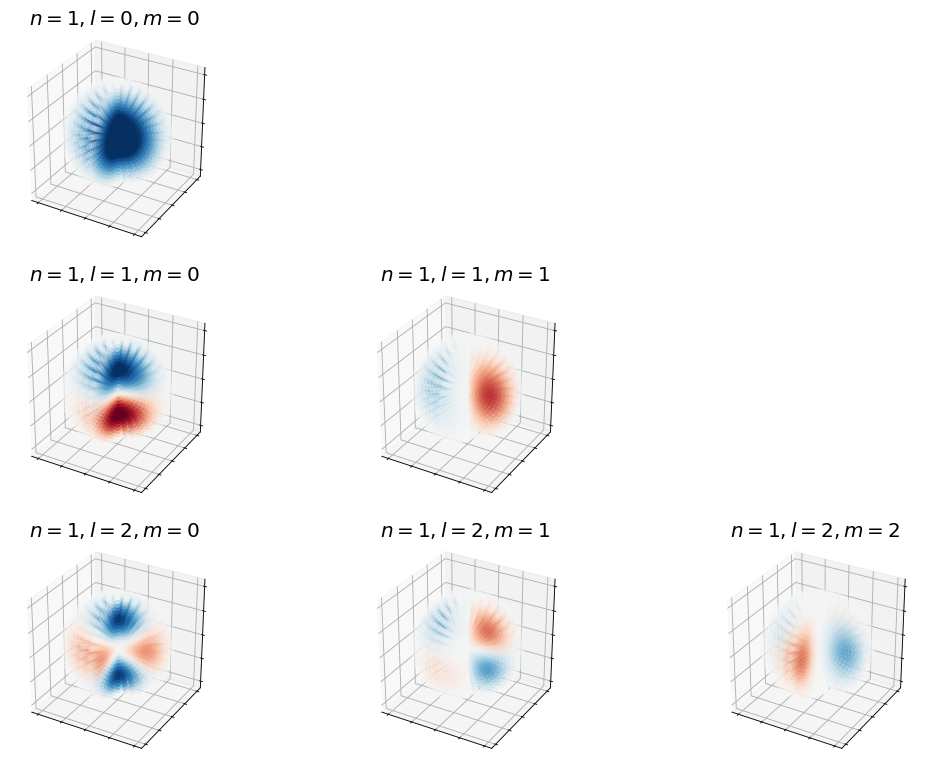

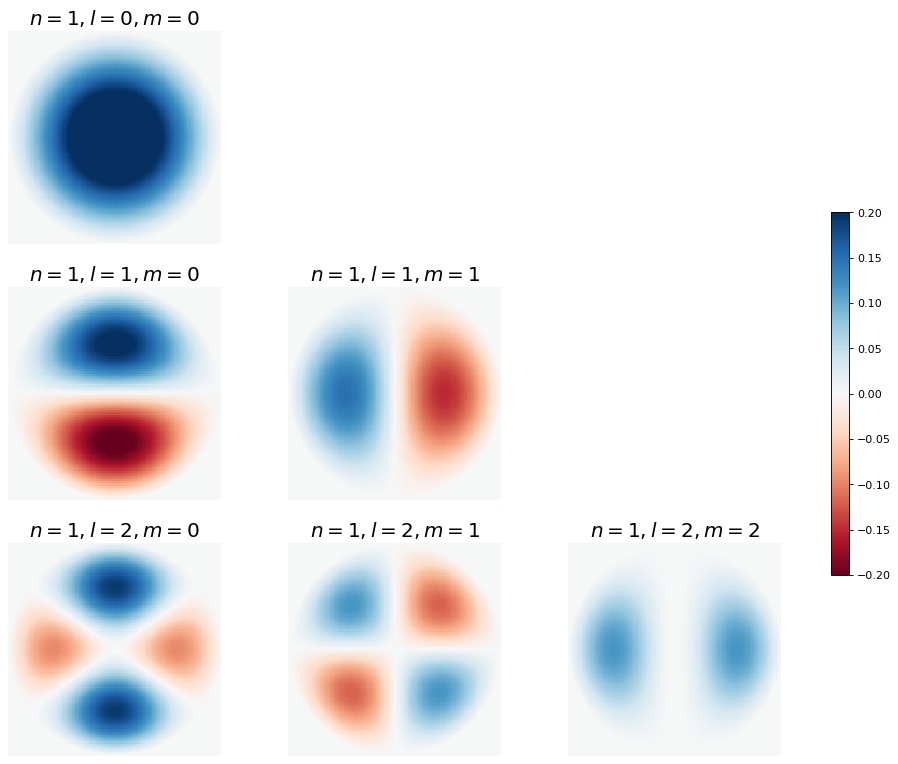

Below, I plot various versions of these functions. First, I investigate how \(n\) and \(l\) affect the wave functions.

Show code cell source

# make two plots of the same spherical harmonic

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from matplotlib import cm, colors

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.special import sph_harm

from scipy.special import spherical_jn

from scipy.special import lpmv

%matplotlib inline

from scipy.optimize import root

def spherical_jn_zero(l, n, ngrid=100):

"""Returns nth zero of spherical bessel function of order l

"""

if l > 0:

# calculate on a sensible grid

x = np.linspace(l, l + 2*n*(np.pi * (np.log(l)+1)), ngrid)

y = spherical_jn(l, x)

# Find m good initial guesses from where y switches sign

diffs = np.sign(y)[1:] - np.sign(y)[:-1]

ind0s = np.where(diffs)[0][:n] # first m times sign of y changes

x0s = x[ind0s]

def fn(x):

return spherical_jn(l, x)

return [root(fn, x0).x[0] for x0 in x0s][-1]

else:

return n*np.pi

def particle_in_sphere_wf(r,theta,phi,n,l,m):

denom = spherical_jn_zero(l, n)

return sph_harm(m, l, phi, theta).real*spherical_jn(l, r*denom)

def plot_particle_in_sphere_wf(n,l,m, ax_obj, r=np.linspace(0,1,15), theta=np.linspace(0,np.pi,20), phi=np.linspace(0,1.5*np.pi,25)):

R, THETA, PHI = np.meshgrid(r, theta, phi)

R = R.flatten()

THETA = THETA.flatten()

PHI = PHI.flatten()

x = R*np.sin(THETA)*np.cos(PHI)

y = R*np.sin(THETA)*np.sin(PHI)

z = R*np.cos(THETA)

wf = particle_in_sphere_wf(R,THETA,PHI,n,l,m)

# plot

ax_obj.set_title(rf'$n={n},l={l},m={m}$', fontsize=18)

ax_obj.scatter3D(x,y,z,c=wf, cmap='RdBu', vmin=-0.2, vmax=0.2,alpha=0.25)

ax_obj.set_box_aspect((100,100,100))

#ax_obj.set_axis_off()

ax_obj.axes.xaxis.set_ticklabels([])

ax_obj.axes.yaxis.set_ticklabels([])

ax_obj.axes.zaxis.set_ticklabels([])

def plot_particle_in_sphere_wf_xz_projection(n,l,m, ax_obj):

x = np.linspace(-1,1,100)

z = np.linspace(-1,1,100)

y = np.zeros(100)

X, Z= np.meshgrid(x, z)

Y = np.zeros(X.shape)

R = np.sqrt(X*X + Y*Y + Z*Z).flatten()

THETA = np.arccos(Z.flatten()/R)

PHI = np.arctan2(Y,X).flatten()

wf = np.zeros(R.shape)

indeces = np.argwhere(R <= 1)

wf[indeces] = particle_in_sphere_wf(R[indeces],THETA[indeces],PHI[indeces],n,l,m)

wf = wf.reshape(X.shape)

# plot

ax_obj.set_title(rf'$n={n},l={l},m={m}$', fontsize=18)

c = ax_obj.pcolormesh(X, Z, wf, cmap='RdBu', vmin=-0.2, vmax=0.2)

# set the limits of the plot to the limits of the data

ax_obj.axis([-1, 1, -1, 1])

ax_obj.set_aspect('equal')

ax_obj.set_axis_off()

return c

def plot_particle_in_sphere_wf_xy_projection(n,l,m, ax_obj):

x = np.linspace(-1,1,100)

y = np.linspace(-1,1,100)

z = np.zeros(100)

X, Y= np.meshgrid(x, y)

Z = np.zeros(X.shape)

R = np.sqrt(X*X + Y*Y + Z*Z).flatten()

THETA = np.arccos(Z.flatten()/R)

PHI = np.arctan2(Y,X).flatten()

wf = np.zeros(R.shape)

indeces = np.argwhere(R <= 1)

wf[indeces] = particle_in_sphere_wf(R[indeces],THETA[indeces],PHI[indeces],n,l,m)

wf = wf.reshape(X.shape)

# plot

ax_obj.set_title(rf'$n={n},l={l},m={m}$', fontsize=18)

c = ax_obj.pcolormesh(X, Y, wf, cmap='RdBu', vmin=-0.2, vmax=0.2)

# set the limits of the plot to the limits of the data

ax_obj.axis([-1, 1, -1, 1])

ax_obj.set_aspect('equal')

ax_obj.set_axis_off()

return c

Show code cell source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3,3,figsize=(16,12),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k',subplot_kw={'projection': '3d'})

for l in range(3):

for n in range(1,4):

plot_particle_in_sphere_wf(n,l,0,ax[l,n-1])

plt.show();

Show code cell source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3,3,figsize=(16,12),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

for l in range(3):

for n in range(1,4):

c = plot_particle_in_sphere_wf_xz_projection(n,l,0,ax[l,n-1])

cbar = fig.colorbar(c,ax=ax,shrink=0.5)

cbar.ax.tick_params(labelsize=10)

plt.show();

Next we see how \(l\) and \(m\) affect the wave functions.

Show code cell source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3,3,figsize=(16,12),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k',subplot_kw={'projection': '3d'})

for l in range(3):

for m in range(3):

if m <= l:

plot_particle_in_sphere_wf(1,l,m,ax[l,m])

else:

ax[l,m].set_axis_off()

plt.show();

Show code cell source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3,3,figsize=(16,12),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

for l in range(3):

for m in range(3):

if m <= l:

plot_particle_in_sphere_wf_xz_projection(1,l,m,ax[l,m])

else:

ax[l,m].set_axis_off()

cbar = fig.colorbar(c,ax=ax,shrink=0.5)

cbar.ax.tick_params(labelsize=10)

plt.show();

Show code cell source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3,3,figsize=(16,12),dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

for l in range(3):

for m in range(3):

if m <= l:

plot_particle_in_sphere_wf_xy_projection(1,l,m,ax[l,m])

else:

ax[l,m].set_axis_off()

cbar = fig.colorbar(c,ax=ax,shrink=0.5)

cbar.ax.tick_params(labelsize=10)

plt.show();