4.3.2. Heat Work and Calculating \(\Delta U\)#

4.3.3. Learning goals for today:#

Express \(\Delta U\) in terms of heat and work

Describe the sign convention for heat and work

Compute the internal energy of an ideal gas given the number of moles and temperature

Compute \(\Delta U\), \(q\), and \(w\) for a reversible isothermal ideal gas expansion

Compute \(w\) for an ideal gas expansion at constant external pressure

4.3.3.1. \(U\), \(\Delta U\), and \(dU\)#

\(U\) - the internal energy

\(\Delta U\) - the change in internal energy (finite difference)

\(dU\) - the differential of internal energy (infinitesimal difference)

\(U\) is the internal energy and is a measure of all energy in the system (e.g. kinetic and potential). The absolute value of \(U\) is unimportant for Thermodynamic processes, the change in \(U\) that occurs during the process is of more import. The change in internal energy for a system to go from an initial state to a final state is:

\(\Delta U_{sys} = U_{sys}^{final} - U_{sys}^{initial}\).

Since the internal energy is a state function, it has an exact differential. If we consider the internal energy, \(U(S,V)\), as a function of entropy, \(S\), and volume, \(V\), of the system, we can write

\(dU = \left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial S}\right) dS + \left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial V}\right)dV\).

This is analagous to writing the exact differential of \(f(x,y)\) as

\(df = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right) dx + \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\right)dy\).

\(\Delta U\) and \(dU\) are related by integration from initial to final states:

\(\Delta U = \int_{initial}^{final} dU\)

4.3.3.2. Heat Capacity#

The heat capacity of a substance at constant volume, \(C_V\) is related to the internal energy of the system. Specifically, the heat capacity is the amount of energy it takes to raise the temperature of a system by 1 degree Kelvin or Celsius. This written as

\(C_V = \left(\frac{dU}{dT}\right)_V\),

where the subscript \(V\) denotes at constant volume.

4.3.3.3. Work and Heat#

The change in internal energy for a system can be expressed as the amount of work done by/to the system plus the amount of heat transferred to/from the system. This can be written mathematically as

\(\Delta U = q + w\)

or, equivalently

\(dU = \delta q + \delta w\),

where the \(\delta\) symbol denotes a path dependent differential. Notice that

\(q = \int\delta q\)

and

\(w = \int\delta w\).

4.3.3.3.1. Sign Convention for Work and Heat#

There is a sign convention for work and heat. It is defined relative to the system. Work done by a system is negative, work done to a system is positive.

\( w < 0\) \(\Rightarrow\) work done by the system

\( w > 0\) \(\Rightarrow\) work done to the system

Similarly for heat, heat given off by the system is negative and heat absorbed by the system is positive.

\( q < 0\) \(\Rightarrow\) heat given off by the system

\( q > 0\) \(\Rightarrow\) heat absorbed by the system

4.3.3.3.2. Computing Work and Heat#

The amount of work done during a process or heat given off or absorbed during a process are important quantities. So how do we compute them?

Typically, it is not possible (or easy) to compute \(q\) directly. Rather, we compute \(\Delta U\) and \(w\) and use the relationship \(\Delta U = q + w\) to compute \(q\). To compute \(w\), we use the relationship

\(\delta w = -P_{ext} dV\).

We integrate both sides and get

\(w = -\int P_{ext} dV\).

\(P_{ext}\) denotes the pressure of the surroundings, not the system. So we cannot simply plug in the equation of state for the system here except for reversible processes.

4.3.3.4. Ideal Gas Expansion and Contraction#

We will use the expansion and contraction of an ideal gas as an example process to understand and compute the change in internal energy, work, and heat (and other quantities). Ideal gasses are chosen because the equation of state (ideal gas law, \(PV=nRT\)) is known for this system. Ultimately we hope that what we learn about these processes is applicable to biochemical processes.

Today, we will consider two processes: a reversible isothermal expansion/contraction and expansion/contraction at constant external pressure.

But first, a few words on the internal energy of an ideal gas…

4.3.3.4.1. Internal energy of an ideal gas#

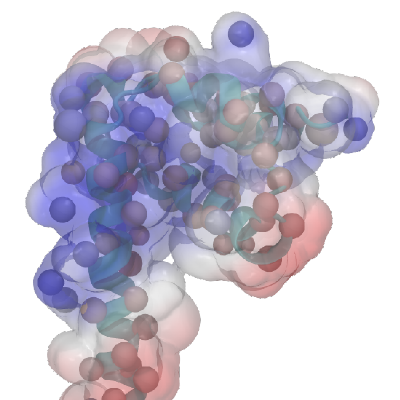

An ideal gas is one in which the individual particles do not interact (no nonbonded interactions). Thus, the internal energy of the system is the kinetic energy of the particles. This can be written as:

\(U_{sys} = \frac{3}{2} nRT\),

where \(n\) is the number of moles of the gas, \(R\) is the universal gas constant, and \(T\) is the temperature.

4.3.3.4.2. Reversible Isothermal Expansion#

Compute the \(\Delta U\), \(q\), and \(w\) for \(n\) moles of an ideal gas when it expands from \(V_1\) to \(V_2\) reversibly and isothermally.

We start by writing out and and all expressions we have for \(\Delta U\), \(q\), and \(w\).

\(\Delta U_{sys} = q + w\)

\(\Delta U_{sys} = U_{sys}^{final} - U_{sys}^{initial}\)

\(U_{sys} = \frac{3}{2}nRT\)

\(w = -\int P_{ext}dV\)

From these equations, we can compute all three! Start with \(\Delta U\):

\(\Delta U = U_{sys}^{final} - U_{sys}^{initial} = \frac{3}{2}nRT^{final} - \frac{3}{2}nRT^{initial} = 0\)

The change in internal energy is zero for an ideal gas undergoing an isothermal process. We now rearrange to see:

\(\Delta U_{sys} = q + w = 0\)

\(\Rightarrow q = -w\)

Now to solve for \(w\):

\(w = -\int P_{ext}dV\)

Because this processes is done reversibly, we know that the pressure of the system is equal to that of the surroundings at every point along the path. Thus, \(P_{ext}=P_{sys}\) and we can plug in the ideal gas law for \(P_{ext}\):

\(w = -\int \frac{nRT}{V}dV\)

Notice \(nRT\) are all constants for an isothermal process so

\(w = -nRT\int \frac{1}{V}dV = -nRT\ln\left(\frac{V_f}{V_i}\right)=nRT\ln\left(\frac{V_i}{V_f}\right)\)

Plug back in for \(q\):

\(q = -w = nRT\ln\left(\frac{V_f}{V_i}\right)\)

4.3.3.4.3. Expansion against Constant External Pressure#

Compute \(w\) for \(n\) moles of an ideal gas when it expands from \(V_1\) to \(V_2\) against a constant external pressure, \(P_{ext}\).

Notice that we are only computing \(w\) here. So we start with

\(w = -\int P_{ext} dV\).

Since \(P_{ext}\) is constant, we can take it out of the integral and simply get:

\(w = -P_{ext}\int dV = -P_{ext}\Delta V\).

Finally, we recognize that the final pressure of the system must be equal to that of the surroundings and thus \(P_{ext} = P_2\), or

\(w = -P_{ext}\Delta V = -P_2\Delta V = \frac{-nRT_2}{V_2}\Delta V\).