4.4.4. Transition State Theory and Temperature Dependence of the Rate Constant#

4.4.4.1. Motivation#

In these notes we will start to investigate some of the quantities that affect the rate constant. We will start by deriving the Transition State Theory version of the rate constant and then look at how this equation depends on temperature.

4.4.4.2. Learning Goals#

After working through these notes, you should be able to:

Derive Transition State Theory expressions for the rate constant

Describe how a rate constant depends on temperature

Identify the correspondence between activation energy and the TST rate constant expression

Compute the activation energy for a reaction from rate constant vs temperature data

Compute the Arhenius prefactor from rate constant vs temperature data

4.4.4.3. Coding Concepts#

The following coding concepts are used in this notebook:

4.4.4.4. Transition State Theory Expression for the Rate Constant#

So far we have more or less ignored the rate constants and yet the values of these constants has a dramatic effect on the rate of reaction. What are the molecular origins oof these values and why are some reactions faster than others?

Transition State Theory, first developed by Henry Eyring in the early 20th century, provides a model for the rate constant that matches experimental data. This result provides us with some insight into why certain reaction are faster than others.

For this derivation we consider a generic reaction

where the rate law is given as

Transition State Theory postulates the existence of an activated complex (or transition state species) that must be populated before the product is formed. That is, \(A\) and \(B\) are in an initial equilibrium with a high energy intermediate, or transition state, before forming the product, \(P\). The proposed mechanism is written as

The species \(AB^\ddagger\) denotes the transition state and is a considered the molecular “species” at the saddle point in the free energy surface between reactants and products. The initial equilibrium has equilibrium constant

The rate of product formation, under the current proposed mechanism, is

When developing rate laws from mechanisms, we avoid writing the overall rate law in terms of intermediates. Thus, we replace \([AB^\ddagger]\) with the equilibrium constant expression above to get

If we compare this to the overall rate law we see that or TST mechanism suggests that

To further investigate the physical underpinnings of \(k_2\) and \(K_C^\ddagger\) we will use aspects of Statistical Thermodynamics. First, we recognize that \(k_2\) is related to the frequency of motion along the reaction coordinate (rc), \(\nu_{rc}\):

Sometimes it is stated that \(k_2 = \kappa \nu_{rc}\) where \(\kappa\) is the transmission coefficient that dictates the fraction of vibrations in this direction that lead to product formation. Here will will simply use that \(\kappa = 1\).

Second, we will express the equilibrium constant in terms of partition functions

we will then extract from \(q_{AB^\ddagger}\) the motion along the reaction coordinate. That is we will dictate that \(q_{AB^\ddagger} = q_{rc}q_{int}\) yielding

where \(K_C^{\ddagger*}\) is the equilibrium constant between TS and reactants with the 1D motion along the reaction coordinate of the TS removed. It can be shown that

Thus yielding

Recall that the equlibrium constant can be expressed as \(K^\ddagger = e^{-\Delta G^{\ddagger\circ}/RT}\) yielding

\(k_2\), the rate constant of the second step in the TST mechanism, is related to the frequency that the complexes cross over the barrier. It can be shown that, under consideration of one dimensional motion at the TS, that

Thus yielding the final expression for the TST rate constant of

This form of the TST rate constant expression is for a second order reaction. More generally, we can write

where \(m\) is the order of the reaction.

The TST expression for the rate constant indicates that the overall rate constant will increase with:

Increasing temperature

Decreasing \(\Delta H^\ddagger\)

Increasing \(\Delta S^\ddagger\).

\(\Delta H^\ddagger\) is related to the activation energy of the reaction and \(\Delta S^\ddagger\) is related to the relative disorder of the TS and reactants.

4.4.4.5. The Temperature Depedence of the Rate Constant#

4.4.4.5.1. Arhenius Expression#

A simpler expression for the rate constant come from Arhenius. He expressed the rate constant as

where \(A\) is the Arhenius prefactor and assumed to be temperature independent and \(E_a\) is the activation energy of the reaction. The linear form of the Arhenius equation is

This expression demonstrates that the log of a rate constant following the Arhenius expression will be linear with respect to \(1/T\).

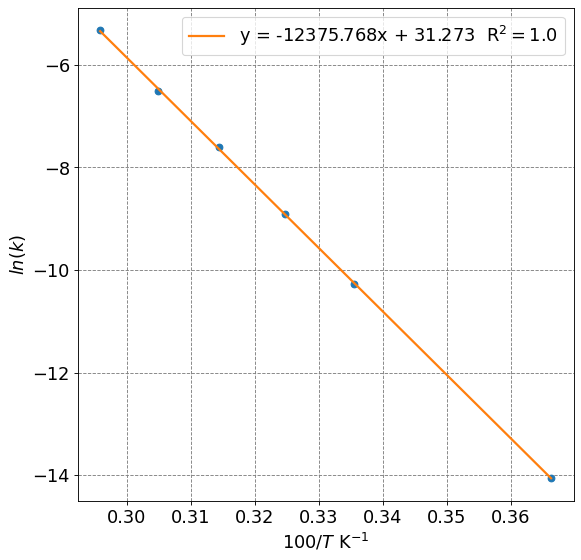

Arhenius plots can be used to estimate the activation energy for a reaction.

4.4.4.5.2. Example: Activation Energy from Arhenius Plot#

The rate constant for the first order reaction

is measured as a function of temperature. From the table blelow determine the activation and Arhenius prexponential factor assuming Arhenius behavior.

T/K |

273 |

298 |

308 |

318 |

328 |

338 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

k/\(10^{-5}\) s\(^{-1}\) |

0.0787 |

3.46 |

13.5 |

49.8 |

150 |

487 |

To determine the activation energy, \(E_a\), and the Arhenius prefactor, \(A\), we will fit the following linear equation

To do so, we will plot \(\ln k\) vs \(1/T\)

import numpy as np

T = np.array([273, 298, 308, 318, 328, 338])

k = np.array([0.0787,3.46,13.5,49.8,150,487])*1e-5

print("1/T:", 1/T)

print("ln(k):",np.log(k))

1/T: [0.003663 0.0033557 0.00324675 0.00314465 0.00304878 0.00295858]

ln(k): [-14.05503759 -10.27165688 -8.91023578 -7.60491048 -6.50229017

-5.32466134]

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

# setup plot parameters

fontsize=16

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8,8), dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

ax = plt.subplot(111)

ax.grid(which='major', axis='both', color='#808080', linestyle='--')

ax.set_xlabel("$100/T$ K$^{-1}$",size=fontsize)

ax.set_ylabel("$ln(k)$",size=fontsize)

plt.tick_params(axis='both',labelsize=fontsize)

# plot data

plt.plot(100/T,np.log(k),'o')

# fit line

# Manipulate data to perform fit

X = (1/T).reshape((T.size,1))

# Fit linear model:

reg = LinearRegression().fit(X, np.log(k))

label = "y = " + str(np.round(reg.coef_[0],3)) + "x + " + str(np.round(reg.intercept_,3)) + " R$^2=$" + str(np.round(reg.score(X,np.log(k)),3))

plt.plot(100/T,reg.predict(X),lw=2, label=label)

plt.legend(fontsize=fontsize);

print("Activation energy:", np.round(-reg.coef_[0]*8.314/1000,0), "kJ/mol")

print("Prefactor:", np.exp(reg.intercept_), "1/s")

Activation energy: 103.0 kJ/mol

Prefactor: 38163368393980.85 1/s

From the fit to the line we have that

and

4.4.4.5.3. TST and Arhenius#

The TST expression for the rate constant demonstrates a temperature dependence of both the exponential term and the prefactor. To demonstrate this we must start with a definition of activation energy from the Arhenius equation. That is

Now let’s determine \(\frac{d\ln k_{TST}}{dT}\)

By analogy we can also say that